Democrats Have a Persuasion Problem

The analysis concerning why Kamala Harris failed to defeat Donald Trump in this election has already begun and there is certainly more to come. Some have focused on how different demographic groups voted (or didn’t). Others have focused on the nature and timing of Harris’s entry into the race or the lack of a Democratic primary. Some observers, noting the overall decline in turnout from 2020, have suggested Trump won because of “lost” or “missing” Democratic voters. The problem with these analyses is that they view the election too much as a singular event, and elections do not happen in isolation. There are trends and patterns to be identified if you take a step back.

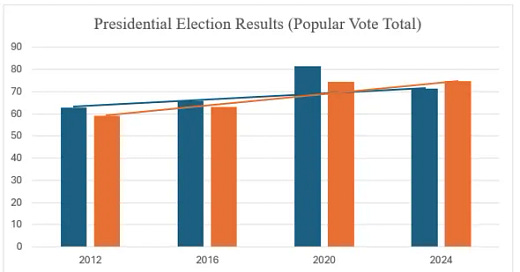

Perhaps the most important of these trends, at least as it relates to understanding the outcome of this election, can be seen in the graph below (Figure 1). The graph shows the Democratic and Republican popular vote totals in each of the last four presidential elections.

The lines connecting 2012 to 2020 show that each party has seen a basic linear growth in its total in the popular vote, except for 2020 when each exceeded the expectation of that linear growth. This immediately eliminates many of the boogeyman explanations of racism, misogyny, and even that of Donald Trump. Female candidates outperformed a male predecessor, and women of color outperformed white women. This nominally rules out both misogyny and racism as primary reasons for Harris’s loss. Donald Trump is also not the answer here. Even if we assume this anti-Trump sentiment only came into play after the 2016 election, when people learned how he would actually govern, it does not explain the decline in Democratic turnout in 2024. If the spike in 2020 was caused by anti-Trump sentiment, that level should have been maintained or increased in 2024, especially with the addition of January 6th after the election. An argument could be made that some of the increase in turnout in 2020 was an anti-Trump surge but then in 2024 voters were tired of this message after nearly ten years of hearing it. To my mind, this would strengthen the larger point of this essay that Democrats suffer from an inability to effectively persuade voters. If an anti-Trump message alone were sufficient to win the necessary votes to win nationally, that should be an easy sell; even life-long Republicans who tend to agree with his policies voted against him.

So why the decline? I would argue that at this point, the question we should be asking is: Why the spike? The only major factor that stands out as unique in the 2020 election is the pandemic. If we accept the overperformance of linear growth of both Biden and Trump as an anomaly of the pandemic, we begin to see a different picture. Those lost or missing 10 million Democratic votes were not reliable Democratic voters. The turnout spike in 2020 represents people who don’t vote regularly but were motivated to vote because of the pandemic and a large majority of them broke for Biden. Exit polls in 2020 indicated that 60% or more of voters who responded that the pandemic was the primary factor determining their vote voted for Biden. Without the pandemic, Harris did not benefit from these extra votes and Trump simply maintained the longer trend of linear growth. This assumption that the large increase in turnout in 2020 was an anomaly of the pandemic is key to the underlying argument of this essay because it allows us to see a larger trend when not viewing elections in isolation.

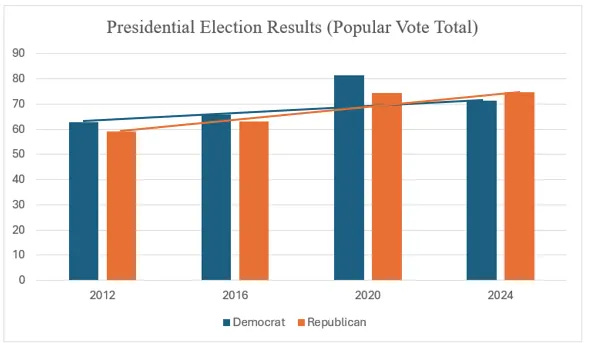

Narrowing the focus to swing states there is another comparison to be made. Figure 2 shows the head-to-head results of the best Democratic result from 2020 or 2024 (Biden or Harris) against Trump’s outcome in 2024 in the six original swing states. This comparison is important because these were the states where the Democratic Party expended the most time, energy, and money during the course of this election cycle.

This graph shows that even if we were to allow Democrats their best outcome over the last two cycles against Trump’s outcome this year, they still would have won only one of the states they knew were going to ultimately determine the outcome. The common arguments about the Electoral College are not useful here because, arguments of fairness notwithstanding, the rules are a set part of the game and Democrats knew this at the outset. They also knew that these were the states where persuading voters was most critical, and they failed.

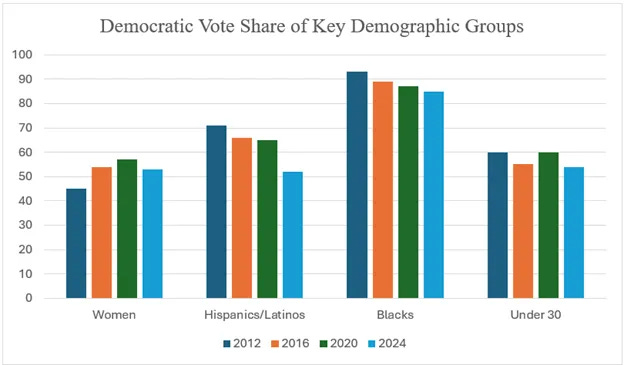

In addition to this geographic failure in 2024, Democrats have failed to make consistent gains among demographic groups that are considered to be the most important to the party’s success — women, Hispanics, Black voters, and voters under 30. Figure 3 shows the Democratic share of the vote from each of these demographic groups in the past four presidential elections. The only group among these in which Democrats have made any gains since 2012 is women and, if exit polling thus far is accurate, that trend was reversed in 2024.

These trends again show a consistent failure to persuade voters among the groups of people who are supposed to be a core part of the party’s base. Democratic campaigning and party building has been based upon protecting women’s rights from a radicalizing Republican party but gains among women appear to have reversed. Democrats have claimed to be the party that will protect minority rights against a growing white nationalism on the right in what will soon be a majority minority nation but have lost in their share among Hispanic and Black voters in each of the cycles analyzed here. Democrats are supposed to be the party of the future, courting young voters to provide better climate, health care, and education policies for them but gains there have not been sustained. It is possible the 2020 numbers shown here for both women and voters under 30 reflect pandemic voting in which case this data would suggest that true trend is one of decline more similar to that among Hispanic and Black voters. Once again there is no single event or candidate that effectively explains these patterns — except for the pandemic. These groups are among the most highly and directly targeted in Democratic campaign efforts and yet they are failing consistently. If the pandemic is indeed the reason for the spike in turnout, the most logical explanation for the larger trend of decline in support for Democrats is that they are simply not sufficiently persuasive to win over targeted voters.

This finally brings us to the main point of analyzing the data in this way: Democrats have a persuasion problem. If you look back at Figure 1, you will notice that while both parties have maintained a basic level of linear growth since 2012, that of the GOP has been slightly greater. Accepting the 2020 totals as a pandemic related outlier, 2024 maintained the normal electoral turnout trend, and the GOP’s advantage in its rate of growth finally allowed it to outpace the Democrats in the popular vote for the first time since 2004. Combining this slower rate of growth with the Democratic Party’s failure to gain supporters in the most critical states this year and declines in support from key demographics in the Democratic coalition, it is clear that Democrats are suffering from a longer-term inability to persuade American voters that their plans and policies are better. Similar breakdowns by issues are more difficult because the same topics are not at the forefront during each election cycle. Nevertheless, a quick analysis of two issues does provide some further insight. In the 2020 election, among voters who said the pandemic was the primary determinant of their vote, a majority voted for Biden. This both explains the surge in turnout during that election, especially for Democrats who saw a larger surge, and the subsequent decline. The state of the economy is an issue that is commonly polled and among voters for whom that was the primary factor in their choice, Democratic performance has plummeted. In 2012 and 2016 Democrats received 47 and 52 percent of the vote of those who said the economy was the most important factor but this number dropped to 16 percent in 2020 and remained only at 19 percent in 2024. This sentiment this year seems to be related to post-pandemic inflation but the fact remains that Democrats were unable to convince voters that the current trajectory or that of a Harris administration would be better than what Trump and Republicans were proposing. We also know that there were several major efforts by influential individuals and groups who typically vote Republican to get like-minded partisans to vote for Harris due to Trump’s actions related to January 6th,, perceived general unfitness for office, and his clear disdain for the rule of law. If we were able to get accurate data as to how many Republicans actually voted for Harris, we might find that subtracting them from her total shows she actually underperformed the linear growth expectation among typical Democratic voters.

Some of the demographic analyses we will see over the next few weeks and months may help indicate more specifically which groups are not being persuaded by Democratic messaging (white women, young men, Latinos, low-income workers, etc.) but they will not provide an obvious scapegoat. Most likely these reports won’t really tell us anything new about who or what issues to focus on because Democrats have been targeting these groups and issues for years; they’re simply not doing a very good job of it. Early exit polling is already indicating that these are some of the groups that did not vote for Harris as anticipated and identifying some of the reasons why. Further analysis and polling will likely hone this down into some pretty fancy looking numbers that show X% more of the Latino vote and she would have won; or that shifts in suburban women voting for other reasons explain this and that margin in certain states. In truth, there will probably be some pretty solid statistical analysis showing both of these along with useful insights into the voting of other demographic groups.

The problem with these perspectives, as stated earlier, is that they only focus on the 2024 election in isolation. This electoral defeat is not because of anything that did or did not happen in 2024. This is not because Joe Biden failed to drop out sooner. This is not because Kamala Harris didn’t differentiate herself enough from Biden. It is not because of inflation, or women, or racism, or voters under 30, or Latinos, or any other specific set of Americans, save for Democrats. As a lesson in why certain groups didn’t vote (or participate) as expected this year, analyses of exit polling may have some value but they do not explain the longer trend of Republican presidential candidates growing their share of the popular vote at a faster rate than Democrats. Nor do they explain why Democrats have consistently lost voter share among key demographic groups central to Democratic efforts. This phenomenon is best explained as a failure by Democrats to persuade new voters. Until Democrats recognize that they have a problem persuading new voters, they will continue to lag behind Republican gains and lose elections. Slogans like “When we vote, we win” are intended to portray optimism and confidence to voters but they also reveal a hidden arrogance in Democratic expectations. Democrats have assumed for too long that demographic changes are on their side and that all they have to do is mobilize these groups that should obviously vote for Democrats. In this emphasis on GOTV efforts, Democrats’ skills in actually convincing voters to embrace their policies have atrophied. Democrats must accept that a strong ground operation focused on GOTV is no longer sufficient. Democrats need to adopt better persuasive language and messaging that appeals broadly to Americans across demographics rather than multiple strains of focused messaging that only insufficiently appeals to specific demographics. To do this, they must do a better job of listening to what Americans are really concerned about and speak to those concerns instead of endlessly repeating platitudes about protecting democracy, fairness, and equality. If Democrats can do that, they might just be able to persuade voters that their vision for America is preferable to that of the opposition.